Blog

Faith, Hope and Charity: Part Two

We rode out of Bombay on a steamy tropical morning in November and picked our way through the squalid shanty towns that sprawl in a stinking mess to the north of the city. The locals, going about their business in the gutters, lined the pavement watching our progress north, their morning fires fuelled by dried cow dung adding to the unique Indian atmosphere. After two frustrating days of mindless bureaucracy we had finally managed to spring our bikes from the Indian Customs and were now ready to take up the challenge that had been left us. A mad and impossible four day, 1,500 mile dash through the guts of India to Kathmandu to catch two friends before they went trekking into the Himalayas without us.

We had woken early, after a mostly sleepless night, thanks to the Indians celebrating Diwali outside our bedroom window and the mosquitoes celebrating the arrival of new blood by drinking ours. We breakfasted on egg and chilli sandwiches and cups of chai and then prepared ourselves to do battle with the 750 million Indians (now 1.5 billion) who all seemed to have congregated on the national highway, which looked more like a neglected British ‘B’ road after a particularly nasty winter.

Whilst dodging what appeared to be the contents of several large zoos, intermingled with a million erratic bicycles, we travelled down roads composed mainly of potholes at alarming speeds. Thanks to the soft BMW suspension we sat comfortably in the saddles as the forks worked triple time and our eyes surveyed the obstacle course before us, which could be best described as a farmyard version of London in the rush hour. The Tata trucks, decorated like mobile Christmas trees trailing clouds of thick black smoke and usually devoid of any useful ornamentation such as mirrors, turn signals or brake lights, would invariably come at us two abreast, forcing our bikes to run for cover off road. We found that the suspension not only coped well on the poor road surfaces but also with the frequent unmarked speed bumps which we would invariably hit at speeds over 50mph. A good set of air horns would have come in handy, especially in the towns where a definite pecking order has evolved – a sort of caste system for road-users. You’d think that the mighty Tata trucks that carve their way through the crowds would be on top of the list but even these give way to the undisputed king of the road the holy cow. The cow – which meanders aimlessly in and out of the traffic – should be avoided at all costs. Running over a cow (if that is at all possible on a motorcycle) is an extremely serious offence – punishable by God. Killing a cow in a Hindu’s eyes is worse than killing his mother – best avoided.

We decided to restrict our riding to daylight hours only, after noticing the quaint Indian custom of piling rocks around broken down vehicles in the middle of the road and then driving off leaving the rocks behind. This, along with cows asleep all over the highway, persuaded us that we would be better off resting. We complimented ourselves on having managed 440 miles in eleven hours without having run into anything, or over anyone, and only having to make one stop for fuel. After the Middle-East, petrol at super inflated prices came as a bit of a shock, especially when during the next day the filthy, low octane stuff blocked up the jets in the carburettors. Fortunately the quick release float bowls on the carburettors made cleaning, them a fairly easy task once we diagnosed the problem.

We pushed on, fighting our way through the hopelessly congested and unsignposted cities, taking occasional breaks at truck stops, resting on charpoys (short beds made from timber and rope), eating a little curry and carrying on. By the end of the second day we had skirted the Thar desert in Rajasthan. By the end of the third we had crossed Uttar Pradesh, following the Ganges as it flowed east, and at the end of this exhausting 400 mile ride we found ouselves in a narrow dead-end street in Kanpur looking for a room for the night. On finding the hotel full we attempted to back-up, but our efforts were thwarted when a brass band, complete with motorised escort, took a wrong turn and came marching in behind us, intent on celebrating Diwali with or without our co-operation. It took 30 minutes of high farce before we could organize them to back up and escape the mayhem.

Travelling through India on any machinery designed after the 1950s attracted the sort of attention that only Royal Weddings manage in Great Britain – chaotic, completely unreasonable, and only ending in separation after much high-profile difficulty. Every time we stopped, the crowds would gather at an alarming rate, prodding and poking first the bikes and then us. On noticing the second cylinder they would decide that the bike had two engines and then want to know how many cc’s and horse power this fantastic machine possessed. They couldn’t quite grasp that it could have as many as 50bhp so would usually assume that we had misunderstood the question. Suspecting that it was a diesel engine, they would then want to know what fuel we used. Max, tired of the same line of questioning time after time, eventually claimed that his ran on coal and water. We would leave them trying to get to grips with his idea and go and look for some accommodation with a haven for our rare steam machines. This would usually necessitate riding the iron horses through hotel foyers or, on one occasion, into the restaurant where we could keep our eyes on them.

On the fourth day out of Bombay, National Highway 28 degenerated into islands of road surrounded by dirt along which lorries lumbered like arthritic elephants. The only way to overtake was on the dusty verges on monstrous three foot high corrugations, which had us bouncing up and down using every inch of the suspension and ground clearance, and quite unable to see what we were overtaking for the dust and vibration.

We arrived at the Nepalese border late, after having taken the wrong road and finding it impossible to find a local with any sense of direction. We had ended up in a small village with its entire population surrounding us. Each time we called out the name of the next town on our map they all took one apprehensive step backwards, until someone decided we might actually be talking their language and deciphered our pronunciation – only for us to learn that the remaining 60 miles to Kathmandu took even the local bus driver ten hours. Since he knew where he was going and we didn’t, we decided not to tackle this road at night and booked into a hotel on the border.

The final leg from the border to Kathmandu climbed 8,000 feet into the Himalayas in a magical staircase of unbelievable tight hairpins to the roof of the world. The reward was an unforgettable first sight of Everest. It was strange to think that less than two months before we had been riding on the shores of the Dead Sea, the lowest surface point on the earth. We later learnt that Land Rovers had to make three point turns to tackle some of the bends, but the BMWs handled this lock-to-lock stuff well. Mid-bend bumps were many but created no problems, one having Max’s bike airborne as he exited a left hand switchback, landing just in time for Max to drop it into the next right. With aching muscles and one split fuel tank we arrived in Kathmandu to find that we had missed our friends by just six hours! Our telegram from Bombay had never reached them.

We finally caught up with them on the other side of Nepal, where we revelled in an unforgettable month of trekkking up to 14,500 feet, white-water rafting and riding elephants through the lowland jungles. It was here that Max, whilst trying to ford a river, missed the crossing point and nearly submerged the whole bike before reaching the other side. Later the crash bar on Mark’s bike dug into the bank on a narrow, crumbling footpath. The bike did a sideways 360 into the field six feet below and may have come off much worse if Mark hadn’t cushioned the blow with his body.

Back in India we spent a few days in Varanisi on the banks of the Ganges watching the Indian tourists drink the holy waters just downriver from where the locals were doing their washing and the remains from cremations were being consigned to the sacred laundry.

We spent Christmas Day at the Taj Mahal, then to Delhi to pick up visas for onward-travel and mail from home. Whilst rushing from one side of Delhi to the other in pursuit of this mail, Max set off out of a car park in a large right-hand arc, opening the throttle all the way. As he tried to straighten up, he almost certainly had time to think: “Steering lock” and utter something beginning with ‘f when he was unceremoniously dumped on the concrete with the ‘uck’ still on his lips. To this day, Max can still be heard to murmur “Integrated steering locks” in his sleep. As in all good cock-ups the mail, naturally, had already been redirected back to England.

Leaving Delhi we crossed the Thar desert into the tropics below Bombay: a land of beautiful beaches, bananas, coconuts, Catholics and Communists, an incongruous jumble of spices typical of Indian life. We had been accompanied from Rajasthan to the south by an Enfield 350 motorcycle (Madras 1984 vintage), with its owner Barney, from Banbury. Barney had left his Laverda 3C motorcycle at home and picked up the Enfield in Delhi for £780. Apart from fork seals which didn’t on any bumpy Indian roads at over fifty mph, the headlight falling off, the total destruction of the rubbers in the QD wheel, the bushes in the rear shock being pulverised to nothingness, the front brake lever falling off (it never really contributed to braking performance anyway), oil spewing from places it didn’t appear to have any, a few punctures and an engine rebuild, it gave him no trouble at all. India might one day forgive Britain for its Imperial past, but I doubt it’ll ever forgive us for the Enfield.

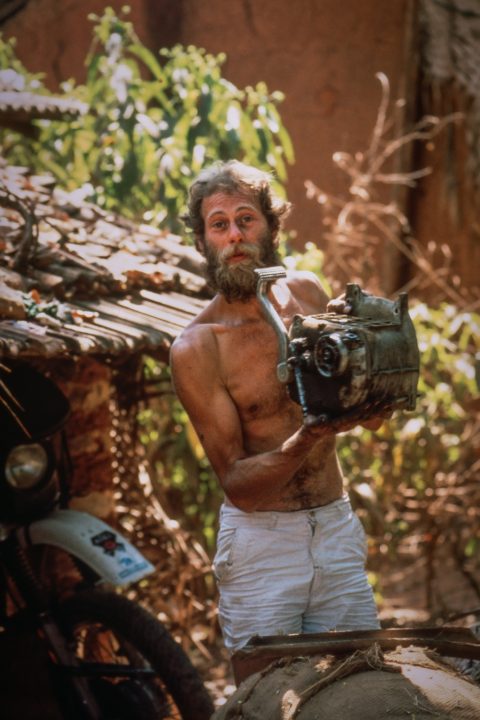

Our first real mechanical problem came in Goa – or more precisely a hundred miles before. Max’s bike refused to change gear so he rode to this tropical paradise stuck in fourth gear, which meant coasting round downhill hairpins – making for a teeth-clenching and unforgettable experience.

Taking temporary residence in a village at the back of a tropical beach we removed the gearbox, breaking the one-piece rust system (exhaust) in the process. Having carelessly failed to pack a BMW workshop in our panniers, we lacked the two BMW special tools deemed necessary to gain entry to the box. We found a mechanic (a man owning both a spanner and a hammer), in the middle of nowhere who helped us undo the output flange nut with a box spanner and a lever between two nuts reinserted in the flange to stop it turning. He then improvised a puller, using his own bicycle axle sawn in half (the only thing we could find with the desired thread); and finally, when we found the offending broken selector pawl spring, topped the whole show by bending a new one over his stove, out of spring wire that happened to be lying around in his shed! We fully intended replacing this at our earliest opportunity, but only got round to it when the bodge broke I5,000 miles later. Never say “impossible” to an Indian mechanic!

Burma (now Myanmar) being closed to road traffic, we next shipped the bikes, uncrated, from Madras to Singapore. When we came to remove them from Singapore docks, however, they insisted that – doubtless due to some local ordnance or dockers’ back-hander – all cargo must leave on the back of a lorry. To comply

with this piece of nonsense we had to hire a lorry, borrow a forklift truck to load the bikes, drive across the customs barrier and borrow another forklift to unload them. Perfectly sensible behaviour.

Singapore offered us a safe sanctuary to recuperate from our travels across the Indian sun-continent and also an opportunity to raise additional funds for the charity.

In Malaysia we had driving rains in their dry season and the realisation that sending our waterproofs back from Greece to save space had been a mistake. We also came face-to-face with Malaysian wildlife when we nearly tripped over a four foot iguana, scaring the living daylights out of us.

After the unpredictable and generally sub-standard roads of the Indian sub-continent, not to mention the self-imposed fifty mph speed limit (which helped ensure Barney could keep up with us without having to do major rebuilds every 500 miles), the joy of riding quickly over the beautifully surfaced Malaysian roads was indescribable. We once again explored the outer edges of our long lasting Metzeler Tyres, whilst sweeping through the jungles and rubber plantations.

We tended to avoid main roads where possible, putting us at the mercy of the cartographers. One wide and freshly-surfaced minor road sped us optimistically over the crest of a hill… and promptly ended. Fortunately we managed to stop without assistance from the many trees surrounding us and vowed to do something unsavoury to the guy who had made the map.

The most exciting Malaysian road was the East-West highway in the north, which carves its sinuous way through the jungle in a riot of fast sweeping bends. These are in excellent condition, except where the local guerillas (of the political kind), had tried to blow them up. The resulting unpopularity of this road meant we could happily take uninhibited racing lines through the majority of the bends, knowing there was nothing more than the odd crater round the next corner.

We arrived in Thailand in time for Songkran, the Holy Water festival celebrating the astrological New Year. The old tradition of monks blessing the people with egg-cupfuls of water poured over the hands has escalated over the years into huge water fights with pickups carrying 44-gallon drums, touring the streets looking for British travellers on BMWs and throwing buckets of icy water over them. By clever use of throttle and brakes whilst overtaking you could get them to throw prematurely thus escaping constant soakings. With both Buddhist monks and policemen in on the fun it was the ideal opportunity to throw a bucket of water over a policeman and not get arrested. A time to avenge all those speeding tickets.

Up into the northern hills of Thailand we were in opium country, the infamous ‘Golden Triangle’ where the locals walk around with knives, crossbows and muskets and where strangers need to smile.

On our way south we passed through Bangkok, city of sex, culture and a million screaming small Japanese motorcycles which taught an ex-despatch rider a thing or two

about riding in heavy traffic. With left and right mirrors swapped, they attempted seemingly impossible gaps at break-neck speed whilst checking that their image remained cool in their vanity mirrors. The one gap palpably unfilled in the busy Bangkok traffic was the one between the riders’ ears.

Heading south again we made a detour to a tropical island where we spent a week relaxing before making our way to Penang and our Indonesian connection, an overnight ferry that would take us to the north of Sumatra. We had only just crossed the equator and were barely half-way down Sumatra when disaster struck. Mark’s right hand crash bar (‘crash’ being the operative word) met with the substantial hub of a pony and cart, destroying his rocker cover and pannier, spraying oil and luggage all over the road. Max, a travelling partner to the last, joined him in a heap on the Sumatran road. The result was two bent bikes and one large crowd.

While Max went to fetch help, Mark was left to persuade fifteen policemen that no, he didn’t use heroin and no, he wasn’t prepared to pay for the damage to a horse and cart that, in any event, had bolted miles into the jungle and yes, he did think Indonesian policemen were wonderful.

After struggling to the port of Padang we arranged for the parts we needed to turn the BMWs back into working motorcycles to be flown to Jakarta on the island of Java. All that remained was to find a way of getting ourselves and the remains of our bikes to Jakarta on the island of..

We patched the Bee-Ems up as best we could – Mark’s now sporting a twelve-piece rocker cover – and made our way down to the docks, where we hitched a ride on a cement freighter. This sloth of the seas took us at seven knots (tail wind permitting), for four and a half days down the Sumatran coast, past Krakatoa, West (not East) of Java, and into Jakarta. It should have taken us four days had the old tub not broken down and drifted for half a day, but there was no hurry as we had to wait to dock or a further two and a half days because Jakarta was more concerned with the holy holiday of Rammadan than with two scruffy British bikers. For the entire week we’d been on an exclusive diet of fish and boiled rice, so when we finally hit land we headed for the nearest cake shop to indulge in eating something that was neither fish or rice.

After picking up the spares we were soon back on the volcanic spine of Indonesia. To make up lost time we crossed java in a week, winding our way up, around and in between volcanoes of every shape, size and degree of malevolence. The climax to this ride came when we rode our bikes into the outer crater of an active volcano, Mt Bromo. We made the final descent at night, over the volcanic ‘Sea of Sand’ which fills it, to witness dawn to the glow from the active inner crater.

From the sublime to the dyspeptic: 24 hours after rising to explore the volcanic wonderland of Bromo we drank ourselves under the table in a Balinese bar with a lethal combination of Bintang beers and ‘Arakataks’ (cocktails made from distilled palm sap).

Unfortunately Max’s mobility and his drinking were slowed down when, five days later, he bounced off a U-turning “bemo’ (taxi) into a tree stump, bending the front of his Beemer yet again. And his leg.

With our Indonesian visas set to expire, we still hadn’t a clue how to get from Indonesia to Australia. The ship we’d relied on to take us from Bali to Darwin turned out to have technical problems: it didn’t exist. Max’s leg got infected. His temperature went up and down – something the R80’s forks couldn’t be persuaded to do. Up s*** creek yet again and not a paddle in sight.

All part of the fun of travelling really.

Will Max Be-eMbalmed or will he recover? Will he be any Bali use if he does? Will we ever stop using these dreadful puns? Find out all this and more in the next thrilling instalment.

Part Three: https://www.markgaler.com/faith-hope-and-charity-part-three

Photo Album: https://adobe.ly/3QTpi16